I’ve emphasized percentage changes over various time spans so far, but there are other ways of reporting the growth of any given prices series.

This inflation formula was preferred by the late Kevin Drum. It’s a 3 month moving average of one month annualized percentage changes. Practically speaking, it’s equivalent to the annualized 3 month percentage change. It’s almost perfectly correlated with it, and the difference between the two is less than rounding error 99% of the time.

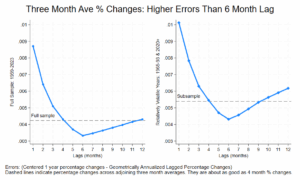

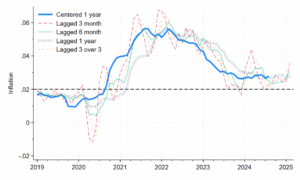

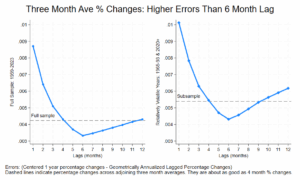

We can also look at the annualized percentage change between adjoining 3 month averages. Using one year centered inflation as a baseline, it has higher errors than the six month percentage change: it does about as well as the 4 month percentage change. Here are the error charts for the full sample and the sample where inflation was more volatile. The dashed lines indicate the 3 over 3 month average errors:

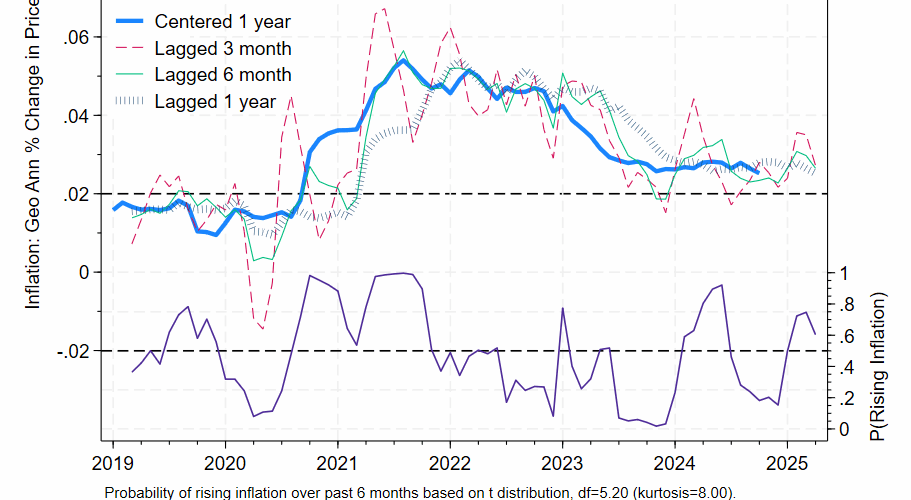

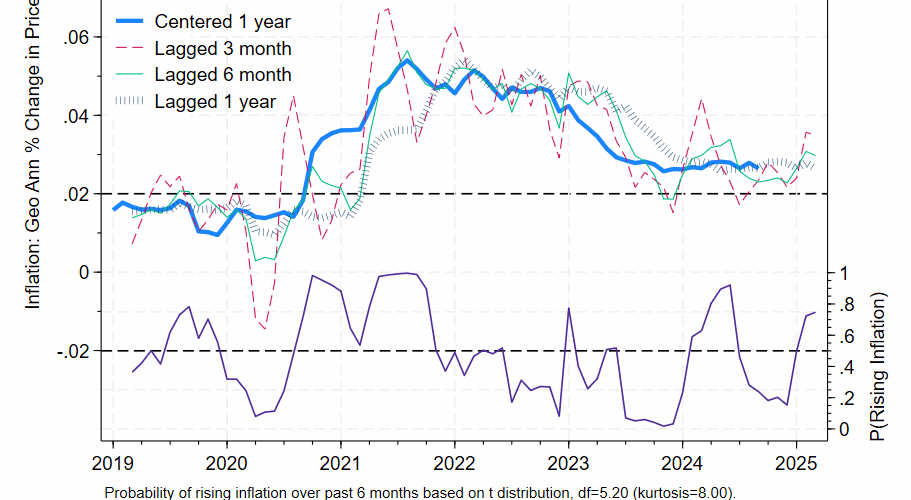

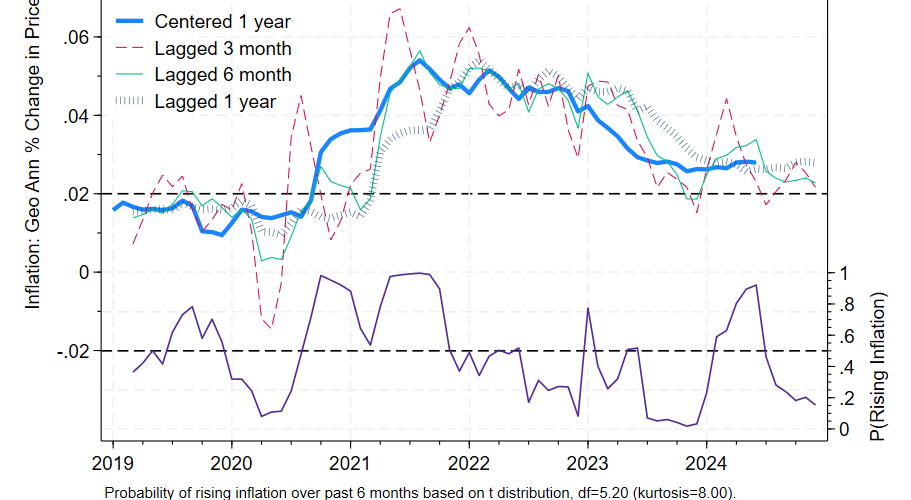

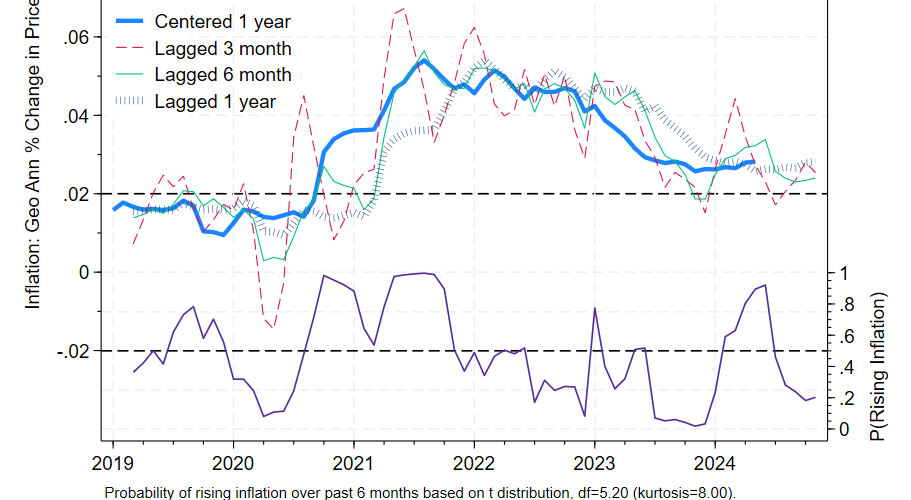

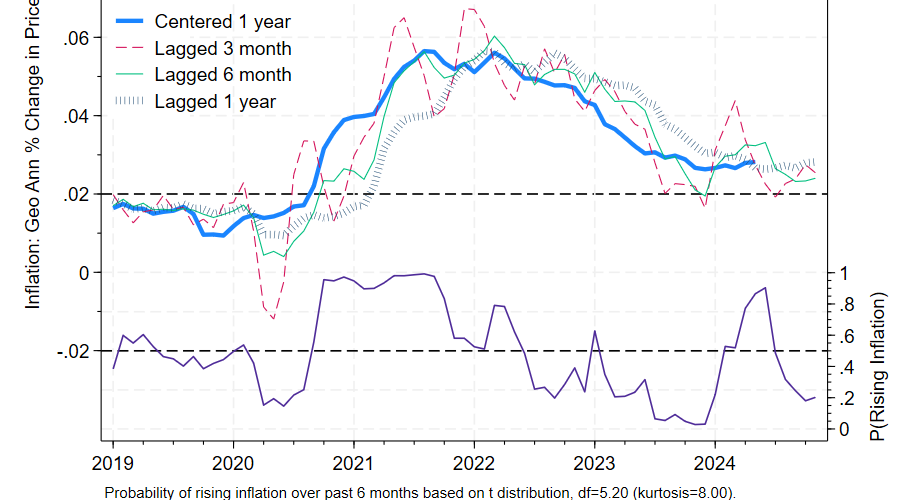

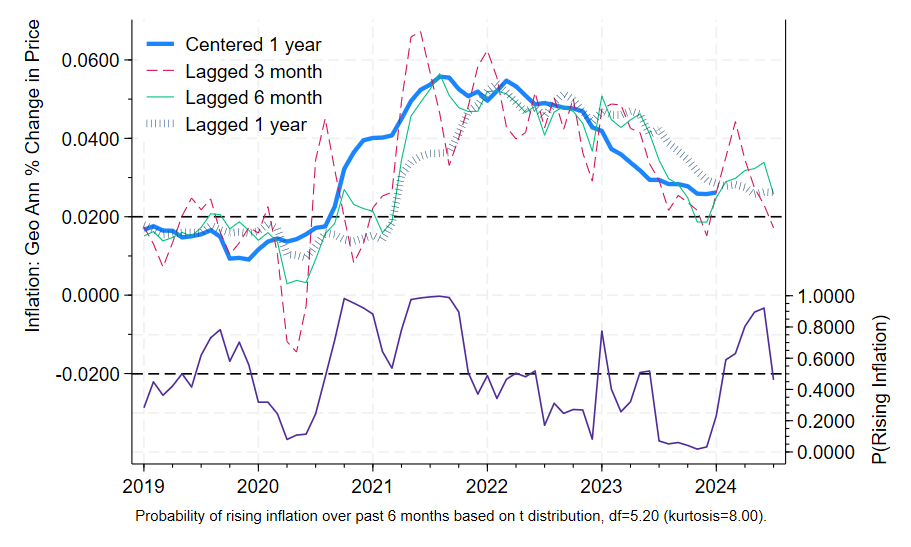

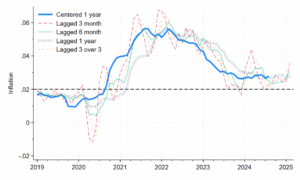

Any 5-8 month percentage change will outperform this metric. You can see that the six month percentage change is visibly better in this timeline:

The thin green lines are generally closer to the thick blue lines, relative to the orange dashed line. The 3 over 3 version is superior to the 3 month percentage change: its correlation with the next month’s 3 month percentage change is .994, where 1.000 is perfect correlation. The 3 over 3 is in a sense more up to date than the 3 month percentage change, but both are noisy.

Ok, but what about 4 over 4, 5 over 5, etc.? None are superior to the 6 or 7 month lag. The percentage change in adjoining four month moving averages represents the sweet spot in this approach, though they are still inferior to the 6 or 7 month percentage change. 4 over 4 has errors only a little higher than the five month percentage change.

Bottom line: stick with the 6 or 7 month geometrically annualized percent change.

Fine Print: All annualization is geometric annualization: see my earlier post or my paper for details. The 3 month moving average is always slightly greater than the 3 month percentage change. Differences can be as high as 2/10ths of a percentage point when inflation is very low (less than 1.5%). The first chart shows mean absolute errors for annualized percent changes at various lags.